The United Kingdom is set to leave the European Union in March 2019. Our research suggests that all likely Brexit outcomes will entail an economic cost for the UK, and these costs would be unevenly spread across different sectors and regions.

The UK’s membership in the EU means that the country enjoys a frictionless trade arrangement embodied in the EU single market and customs union. After exit, barriers to trade in goods and services would increase while labor mobility would fall.

This matters because the EU is the UK’s largest trading partner, accounting for nearly half of the UK’s trade in goods and services. For example, 56 percent of cars produced in the UK are exported to the EU and about ¼ of UK-produced financial services are related to EU clients.

A frictionless border has enabled UK firms to specialize in activities in which they have comparative advantage and the greatest value added. EU membership had also stimulated foreign direct investment as firms invested in the UK as a base to access the single market, while free labor mobility enabled the UK to hire talent from across the EU.

The costs of different Brexit outcomes

Leaving the EU will inevitably reduce or eliminate some of the benefits of frictionless trade. Our study estimates the potential impact from higher trade barriers, lower migration, and lower FDI flows for each economic sector in the UK. For simplicity, we assume that trading relations with non-EU countries remain unchanged.

The EU is the UK’s largest trading partner, accounting for nearly half of the UK’s trade in goods and services.

Since the specific nature of the new economic relationship between the UK and the EU is still unknown, we present estimates of the long-term economic impact under two illustrative scenarios for the post-Brexit relationship.

- An “FTA” scenario, which assumes that the UK and EU reach agreement on a broad free trade pact, including an agreement on services trade, but with some restrictions on migration. In this scenario, UK output will be about 2½ to 4 percent lower in the long run compared to a no-Brexit scenario. This translates into a cost of about £900 to £1300 per capita.

- A “WTO” scenario, in which the UK loses any preferential access to the EU market and adopts WTO tariff schedules for trade in goods. In addition, an even stricter migration regime is assumed. In this scenario, the decline in real output relative to no Brexit would be larger, between 5 and 8 percent in the long run (about £1700 to £2700 per capita). This estimate takes into account the effects of higher trade barriers, potential reductions in foreign direct investment flows, and lower net migration.

Our estimates of the long-term effects of Brexit on the UK economy are similar to those of other analysts.

The economic impact of the deal agreed at the November 2018 EU summit is not modelled; however, our FTA scenario falls in the spectrum of economic outcomes consistent with the Political Declaration.

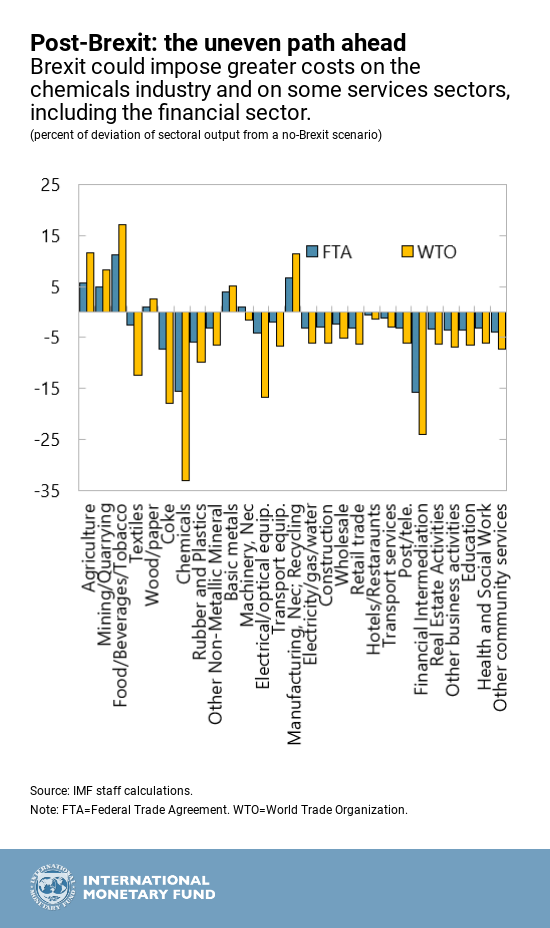

The Brexit impact would differ across sectors

Sectors with stronger trade links with the EU, larger increases in either tariffs or non-tariff costs, or greater sensitivity to price changes would be more affected.

- Among manufacturing sectors, chemicals and transport equipment would be particularly affected due to potentially big increases in trade barriers and their significant integration in the European production supply chain, which could be disrupted post-Brexit.

- The negative effects would be even more pronounced for some service sectors. For example, financial services output could fall by as much as 15 percent in the FTA scenario. This reflects the fact that about one quarter of domestic financial sector revenues are related to EU clients. Firms might need to set up subsidiaries in the EU to continue to provide some of these services.

What does Brexit mean for employment?

Labor availability in sectors that rely more heavily on migrant workers, both low- and high skilled, could be affected by future changes in immigration policy.

Brexit may usher in a prolonged period of higher structural unemployment, reversing some of the impressive employment gains of recent years, as workers separate from highly-affected industries but move only gradually to less-affected sectors and regions.

Active labor market policies such as retraining and assistance with job placement will be critical to facilitate the relocation of workers. The key is to support workers, not specific industries or jobs. Making credit more easily available to entrepreneurs would also enable people to respond flexibly to the new economic reality and increase their productivity. Efforts to boost housing supply should continue to help workers move from more negatively-affected regions to areas where jobs are more plentiful.